The Alchemy of Migration in Comadres

Venezuelan dreamscapers Silvana Trevale and Daniela Benaim combine documentary stylism with surreal craftsmanship to create a photographic series where migrant stories become alchemical tales of renewal and friendship.

18 FEBRUARY 2021

Photography by Silvana Trevale

Styling & Art Direction by Daniela Benaim

Words by Laura Cadena

The practice of being comadres might as well be considered occultism. To be comadres is to have a furtive sisterhood— an intrinsically Latin American bond of friendship that emerges from the complicity that can only be born from shared spaces or shared circumstances for survival.

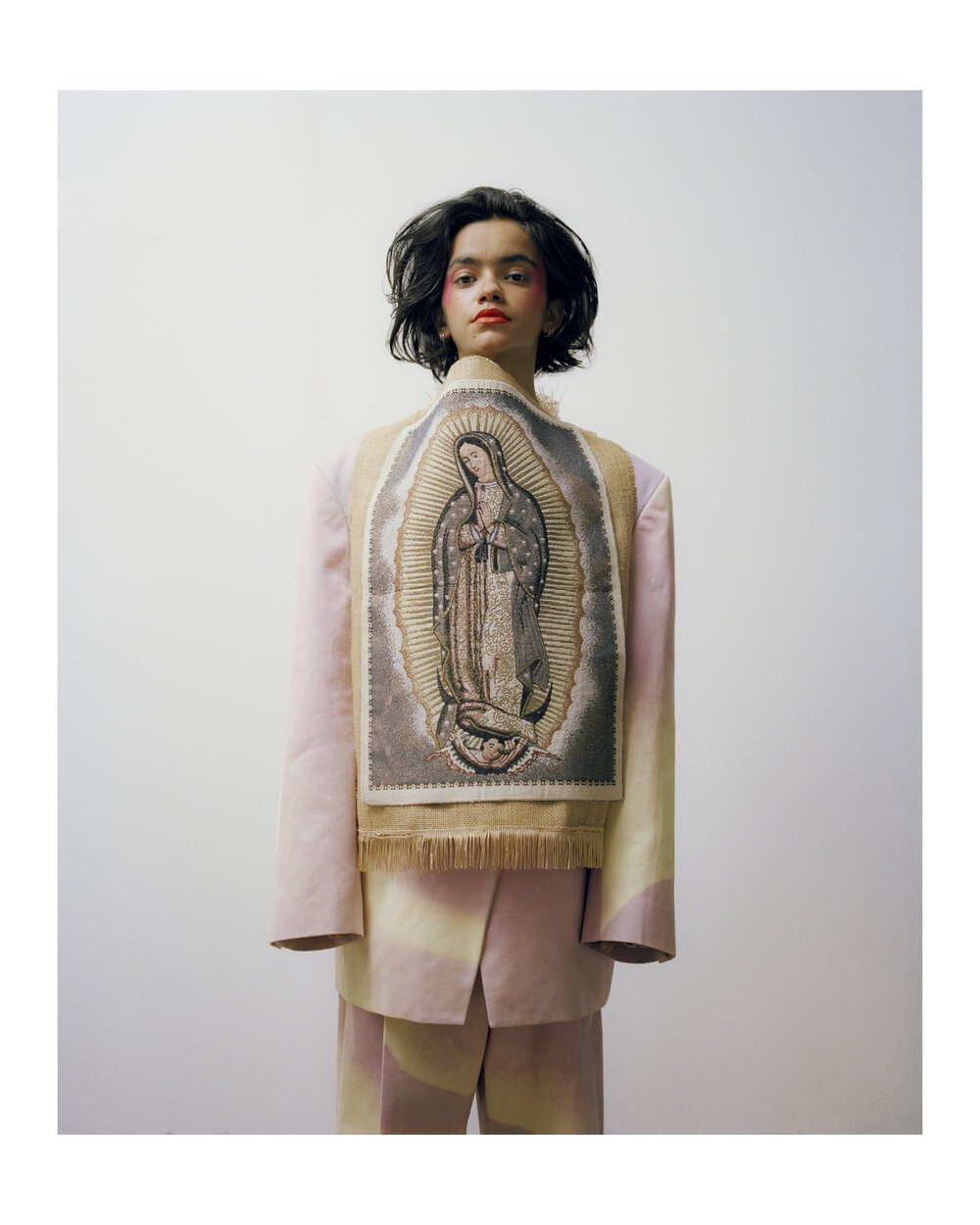

The spirit of being comadres is the animating force behind photographer Silvana Trevale and stylist Daniela Benaim’s latest collaboration— a homage to the syncretic expressions of immigrant life. Featuring London-dwelling Latin American immigrants as models, the theme here is Migration as Alchemical Renewal—departing from the familiar and finding through displacement the exposures that kindle transformation, conversion, disintegration, entanglement, and growth.

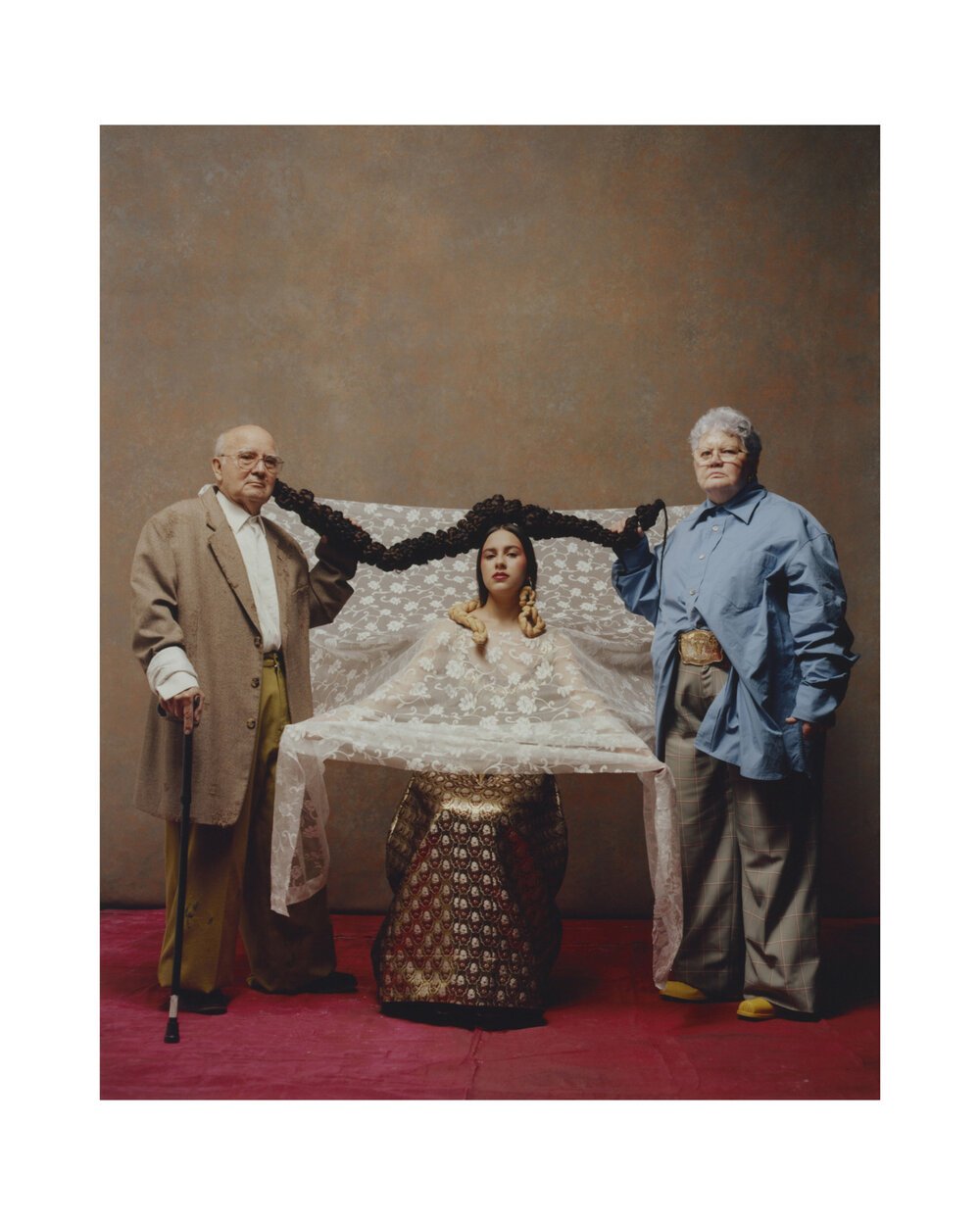

The people photographed in this series don’t just blur boundaries, they use them as tabletops for their experimentation. Take first the image El Mantel— a tribute to the mantel de comedor, a laced, white tablecloth typically used in Latin American households to adorn kitchen or dining room tables. Here, the domestic scene of a family dinner is framed as a surreal ritual in the style of Sergei Parajanov. The head of Jessica Gómez— a young Londoner from a Colombian family— emerges from beneath a mantle with two pieces of braided bread hanging from her ears. Flanking the table which her body has become, Jessica’s grandparents stand like guardians, holding above her a hair-woven Challah.

Both Silvana Trevale and Daniela Benaim are Venezuelan-born women who found each other in London and spun a friendship/collaboration à la Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington: foreigners with a shared fascination for the celestial realm, for all that is feminine, and for potent, magic-driven art-making. For Benaim, this project is the conceptual continuation of her previous series La Casa, in which she did a seven-part photographic study of the home as a hallucinatory, shape-shifting abductress. Whereas in this previous series Benaim frequently wrapped her models in cloth to transform their bodies into limpid, doll-like figures, Comadres depicts unambiguously human bodies that stand firmly within their subsumptions of myth, land, heritage, past, and present. Silvana Trevale’s photography is key in achieving this effect. Opting for the straightforward portraiture-style that defines her documentary work, Trevale creates figures that feel magnanimously statuesque, but somehow familiar—icons for the foreign in a foreign land.

Since 2017, Trevale has been returning to Venezuela yearly to document the daily lives of her countries’ youth. She is committed to changing assumed narratives about what it means to be both Venezuelan and young— two identities whose combination is all too often equated with misfortune. Seeing her work, I think of the following expression: “La historia es reinventada pero el futuro es recordado”// “History is reinvented, but the future is remembered” . In her documentary work, Trevale labours against the forgetfulness of the world. Her work is about opening alternative timelines for Venezuela, despite the doomsday design which conspires towards its erasure. In Comadres, the photo-alchemical operation functions differently: Trevale doesn’t transfuse the present into the future, but instead the past into the present.

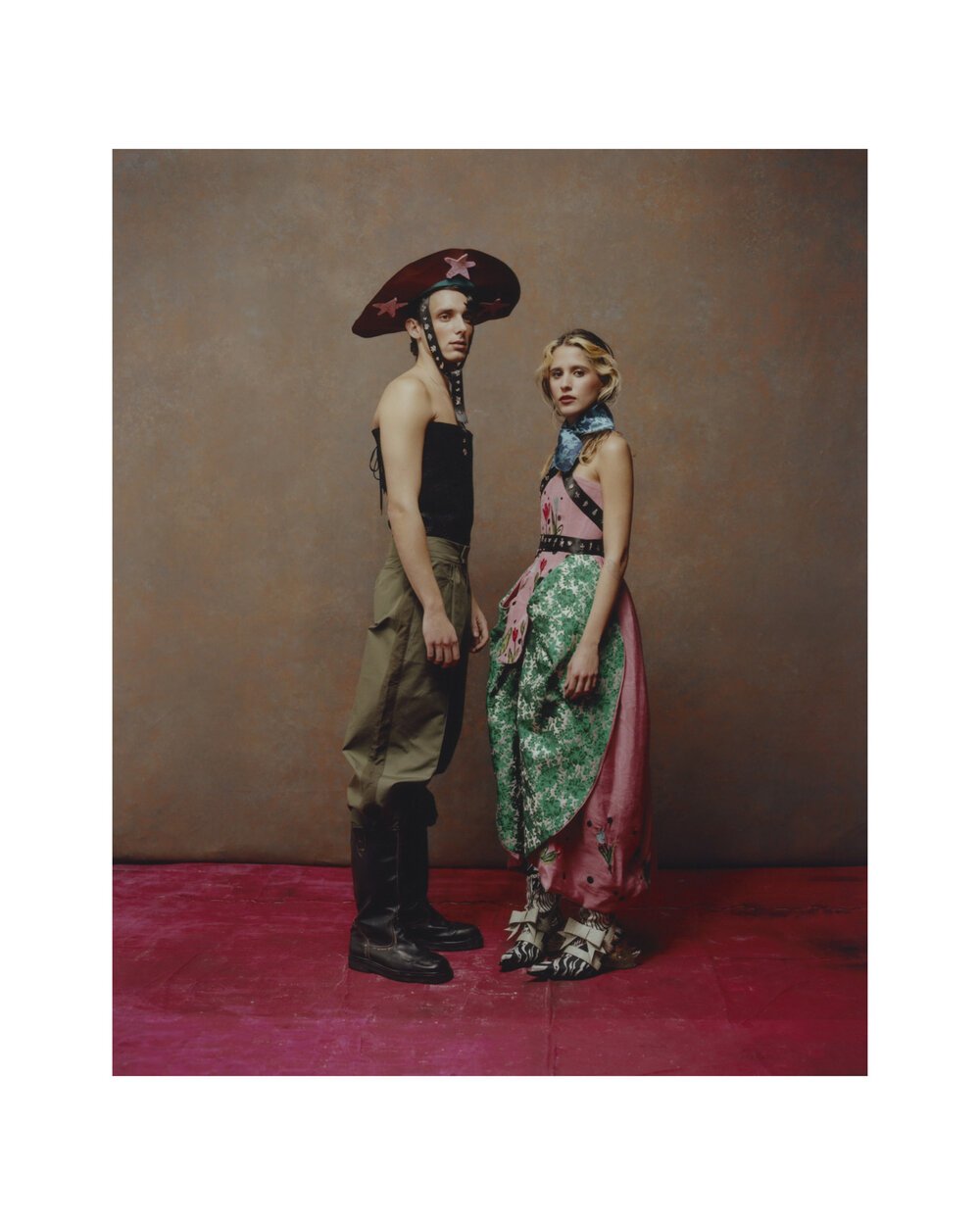

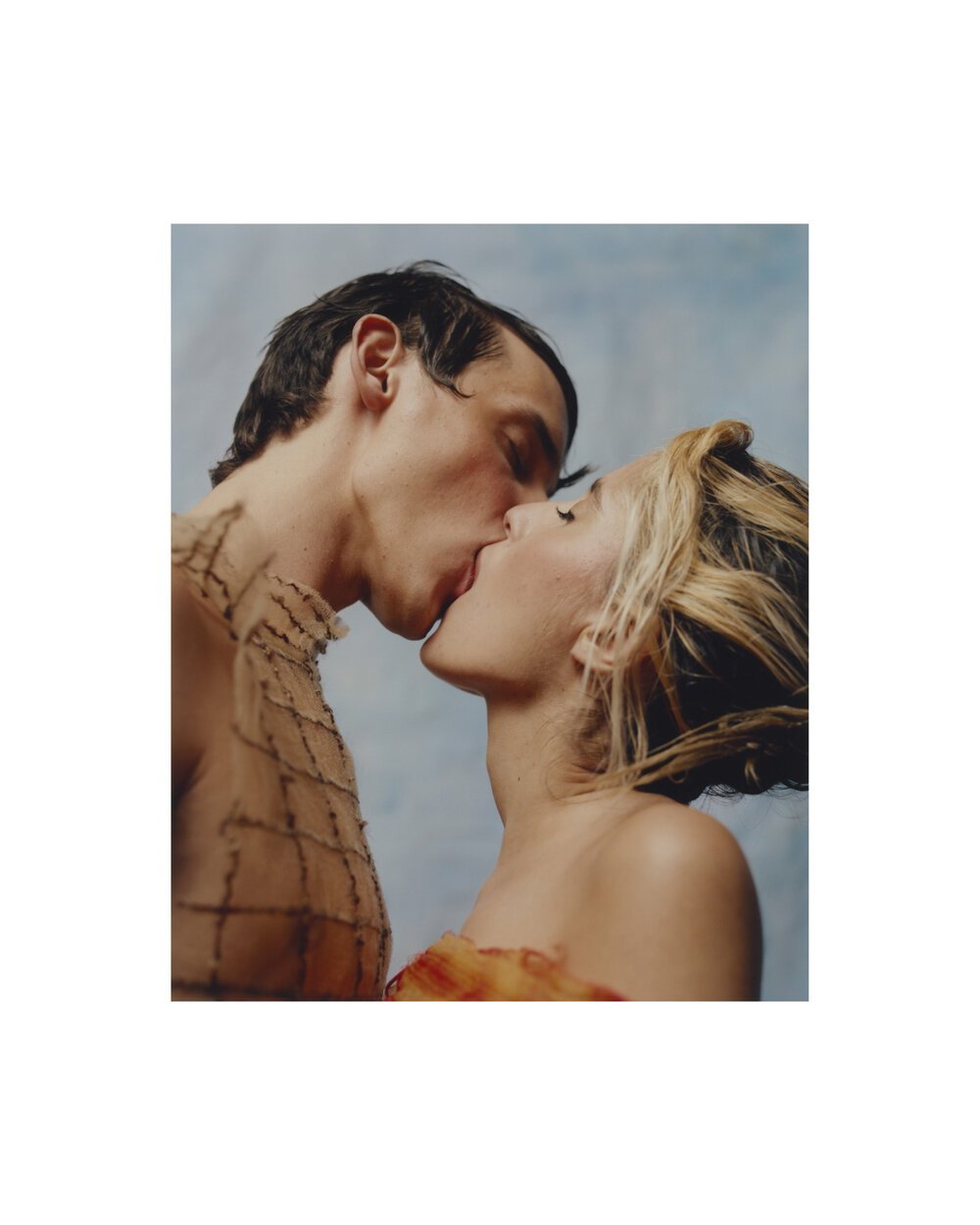

In true comadre- spirit, Trevale and Benaim’s collaboration also extends to all the models they photographed—working with each to create costuming that blends their personal histories with Latin American folktales, artworks, and traditions. For instance, as an homage to the iconic romance of Brazilian bandits Lampãio and Maria Bonita, real-life lovers Helena Cebrian and Lucio Martus embody these figures in a contemporary take on cangaceiro fashion that highlights its complex gender negotiations and predilections toward pirate-like ornamentation. The tricksterism of thi seclectic style is representative of the inventive spirit that Comadres celebrates. This is not a series about preserving histories or traditions. It’s a series about mobilizing them towards re-invention and liberation. Embodiment is everything precisely because it is a force of transformation.

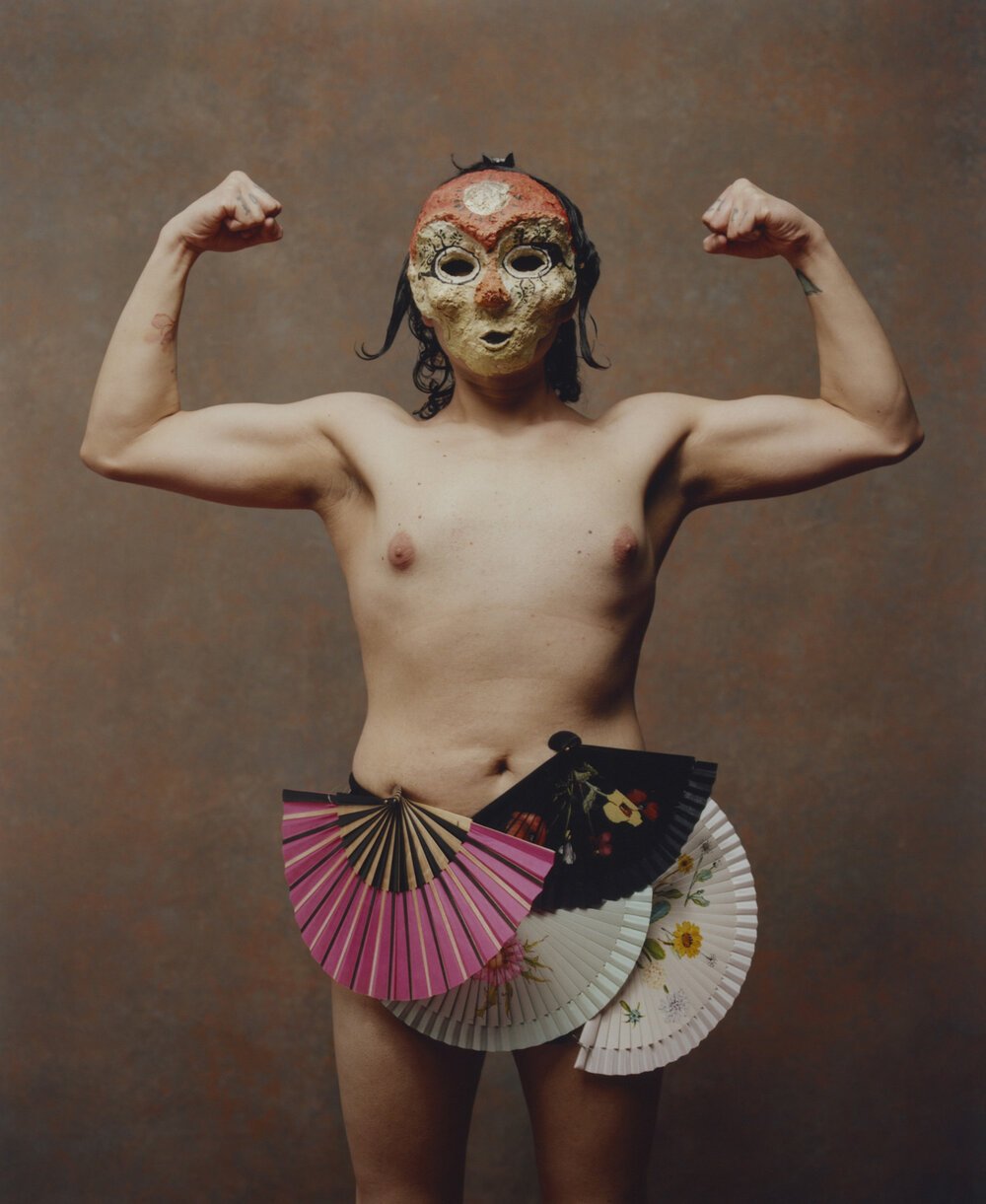

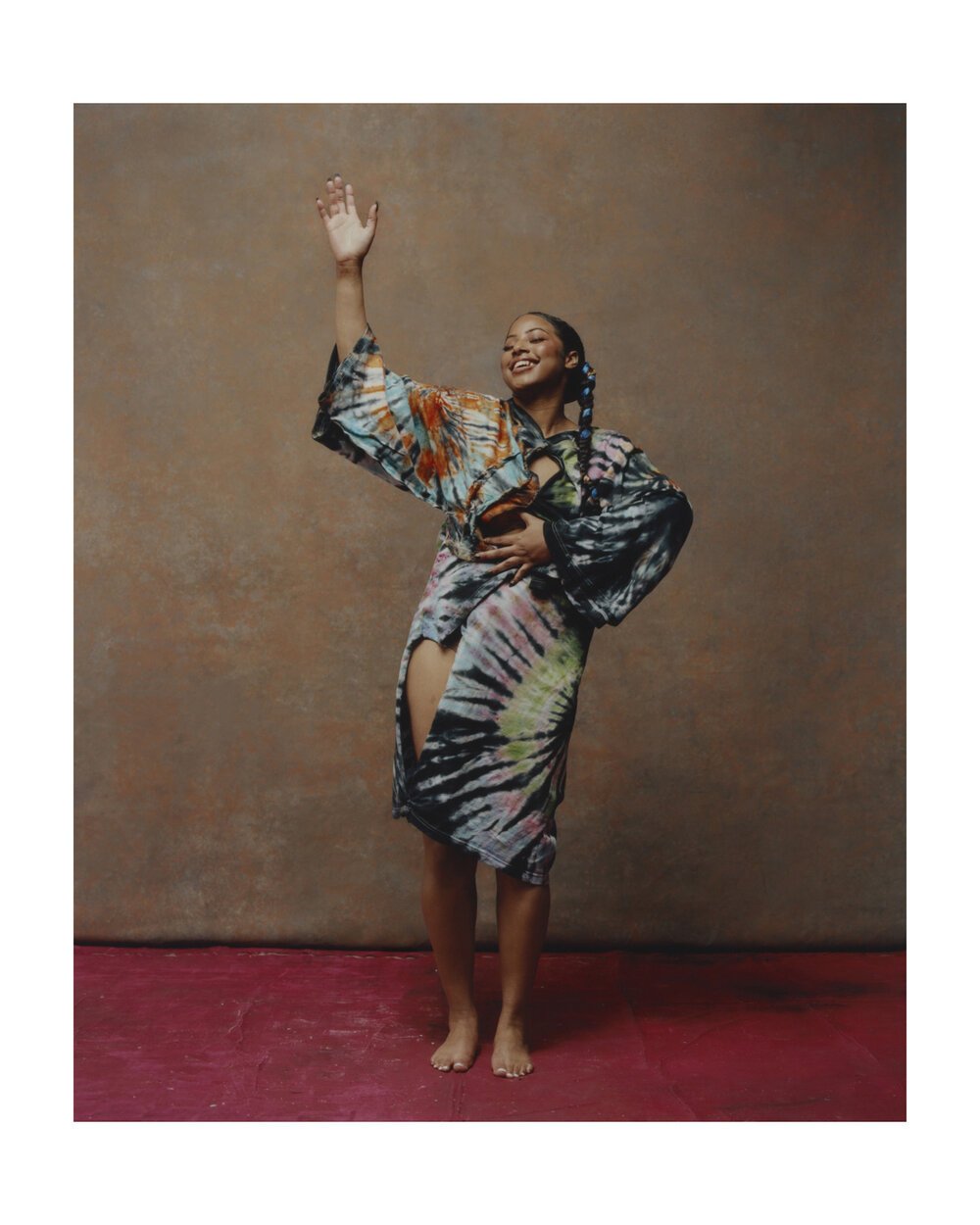

The intention to re-frame tradition is perhaps made most evident by the series’ portrayal of La Burriquita. Emerging circa 1800, La Burriquita is a Venezuelan folkloric dance that combines African, Indigenous, and Spanish song, rhythm, and movement as it theatrically enacts the arrival of a woman riding a donkey into a singing crowd. Traditionally, the woman is nearly always portrayed by a crossdresser who rides atop an elaborately made, toy donkey— a symbol that undoubtedly engages in misogynistic humour. That said, La Burriquita is simultaneously an anti-colonial ridiculation of Spanish colonizers, and has been more recently reclaimed as part of queer folkloric histories.

In Comadre’ s depiction, La Burriquita is modelled by Alonso Gaytan, a transfemme Mexican-born designer who has been living in London for three years. In her picture, she dons a long skirt and a defiant stance, gracefully holding a paper donkey tucked beneath her arm. Looking at this photograph, Alonso shares her thoughts with me: “C lothing can be brutally honest” she says, “It speaks for you whether you want it to or not. Just because of its association with lo femenino [what is femenine], people think of it as frivolous, disingenuous, or even as a disguise. But really it’s quite the opposite. Even La Burriquita proves this. Machismo in Latin America can seem so rigorously strict, but she shows us that it can’t help but lean towards lo femenino”.

With its homages to Walter Mercado and Muxe identity, Comadres celebrates gender-bending as one of the many beautiful renewals spurred by migrational alchemy.

However, as its title makes self-evident, the series honours femme expression with particular avail— dedicating singular tributes to Violeta Parra, La Virgen de Guadalupe, La Llorona, La Malinche, and La Quinceañera.

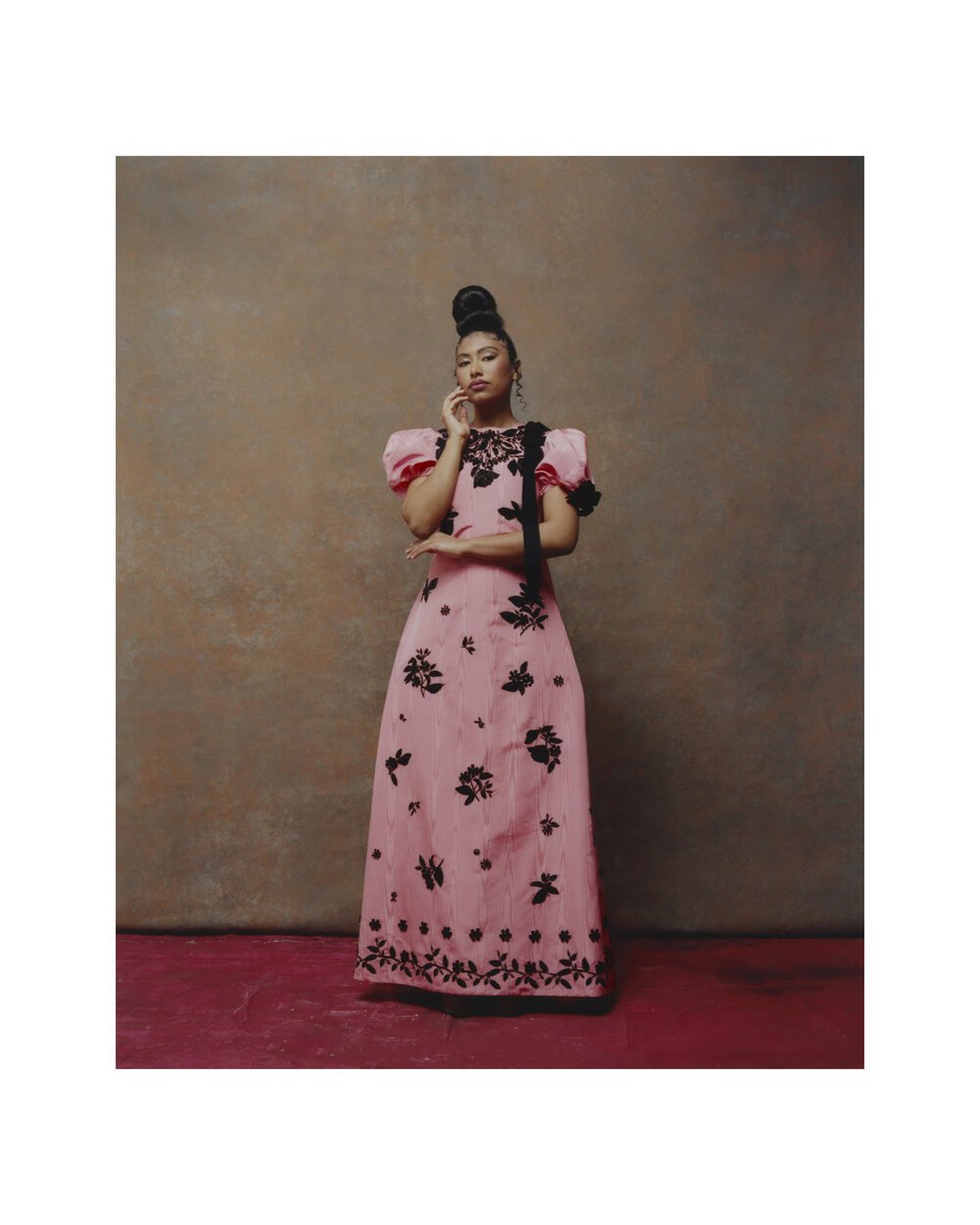

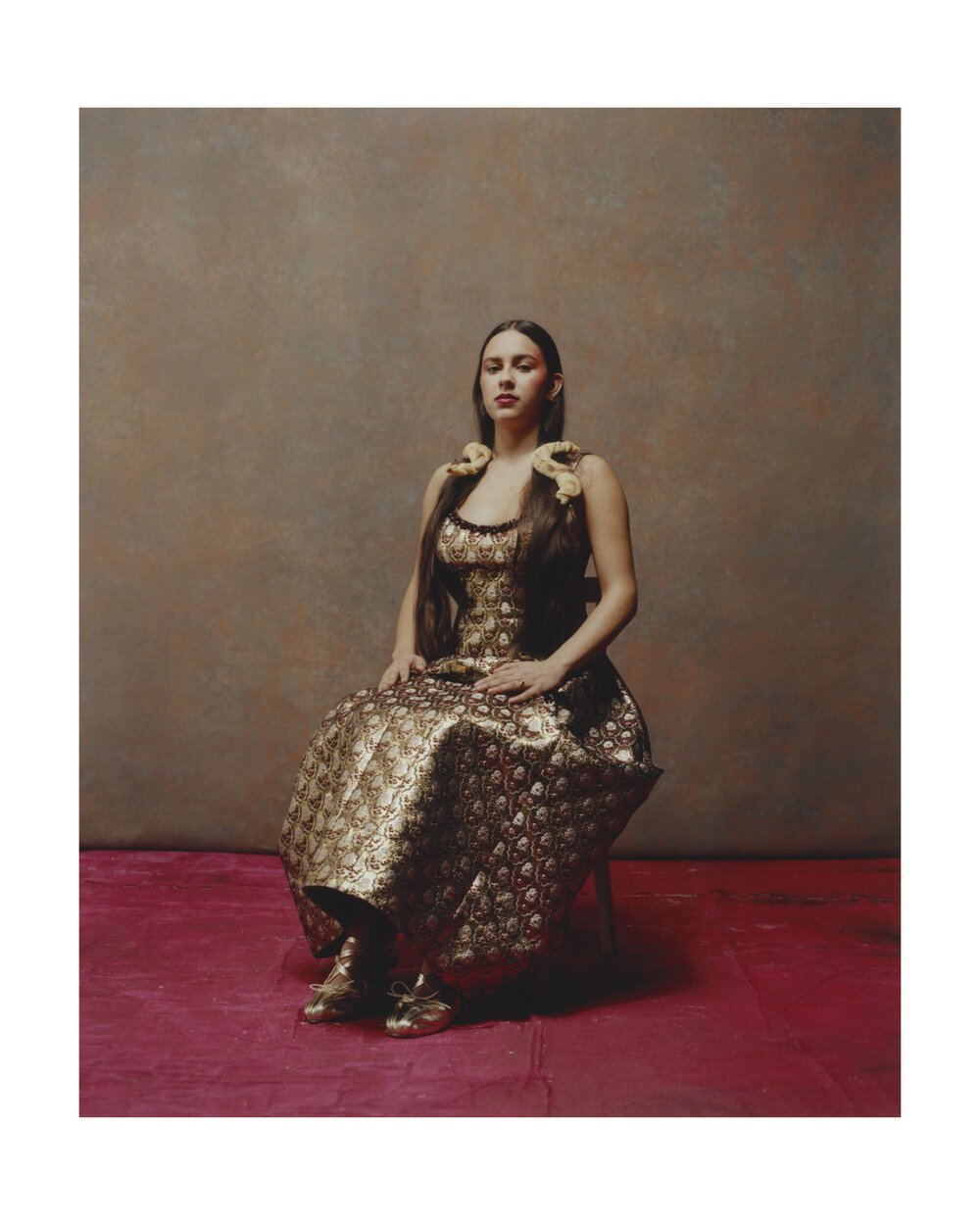

This latter tribute is embodied by Sophie Castillo— a Colombia-born Londoner from mixed Cuban heritage. For her actual quinceañera, a shy, teenage Sophie opted for a small family-gathering and wore a slender, lilac coloured strapless dress. The tradition of a father-daughter dance was adapted in favour of Sophie dancing first with the single-mom who raised her, and then with the three most important men in her life: her stepfather, her uncle Eddie, and Lee (Eddie’s husband). Having an unconventional (or nonexistent) quinceañera is an immigrant rite of passage. Trevale’s magnetic photograph of Sophie in a wide-frame, pink dress—with none other than a bejewelled, baby-face hairline crown— reads as a long-overdue rewrite of what this femme-rite of passage feels like in the 21st century life of an immigrant.

Beyond these personifications, Comadres honours Latinx femininity as it is also embodied by domestic spaces and crafts. Perhaps the first image that comes to mind is the aforementioned El Mantel, in which the laced tablecloth— a product of distinctly feminine craftsmanship— functions as a conduit for intergenerational exchange. “I was the firstborn grandchild. La consentida [the spoiled one]”, El Mantel’s model Jessica tells me over the phone, “I was raised largely by grandparents, and they always loved to dress me like a doll. The memories of my early childhood are mostly of us sitting together, just passing time”.

In this same image, a hair-braided Challah is a nod to Benaim’s Jewish heritage, as well as to the unambiguously feminine divine tasks (mitzvot) of Challah-making and braid-making in Latin America. Describing the 6-strand approach of making her massive hair-sculpture, Afro-Ecuadorian hairstylist Carla Quiñonez Leon loses herself in thought: “I think in my last life I was a hairstylist as well. My hands know things I don’t know. It scares me sometimes! But I also figure it’s my heritage letting itself be shown”.

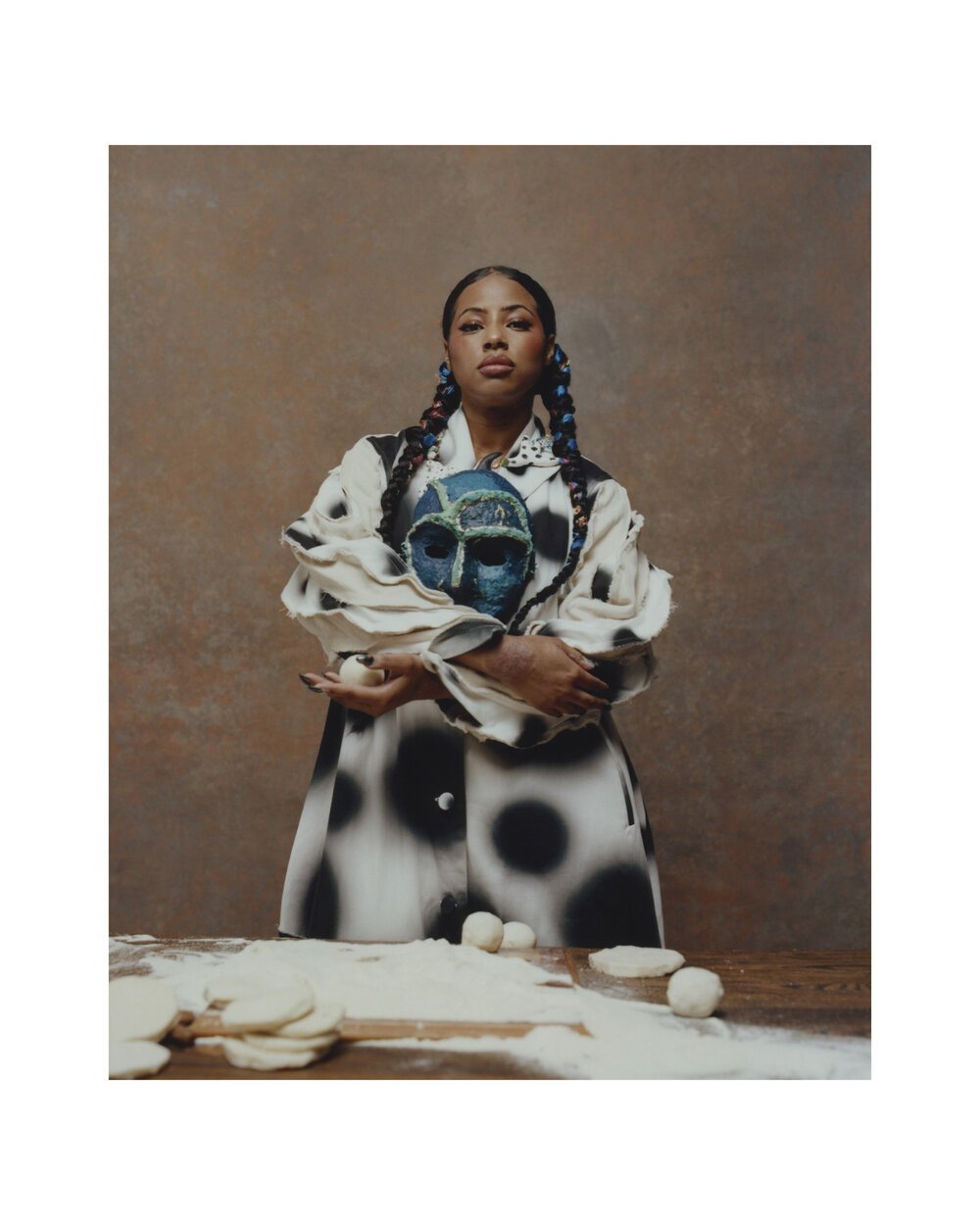

In harmony with El Mantel i s La Cocina (The Kitchen). Here we see the surface of the kitchen table as the site of both female labour and female introspection. Like Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo, Benaim and Trevale share an understanding of cooking as the magical transmutation of substances: an “alchemy for the people''. In their image, Jay-Ann Lopez’s pose hints at ritual, her hands cupping a small, pearl-like ball of masa— the corn-based dough at the bedrock of Latin American cooking traditions.

Looking for a lived understanding of masa, I turned towards my childhood friend and

masa- worker extraordinaire Cristina Serrano, who runs her own cooking business from her home in Bogotá, Colombia. “Masa requires a feminine ethos”, she explains to me, “It’s the closest I’ve ever felt to childrearing— my success depends wholly on the care and patience that I afford the mixture. When you see women working *masa—* most likely without a scale or measuring cup— you can tell how deeply they know its truest form. And yes, the truth of masa is mutable—affected by air, by rain, by a particularly hot morning and by the emotions of the cook— but it's a truth they arrive at time and time again.”

Pressed closely against her breast, the cook in La Cocina holds a blue-green mask— one in a set of two masks commissioned for Comadres from London-based, Iranian artist Kimia Amini. Amini crafted these masks to personify Water and Sunlight— migrational forces with the unique power, in the artist’s own words, “of travelling through most substances and to most places”. The adhesive that binds Amini’s masks together is made from the powder of Eremurus flowers— flowers that of course grow because of light and water’s ability to reach them in the arid grasslands of Iran. From there, their starfish-like roots are pulled, and ground into the powdered substance that travels back to London tucked within Amini’s luggage, another migrant in its own right.

There is no final image that distils the essence of this series. Every photograph is its own sphere of enchantment. That said, The Immigrant m ight be my favourite of the lot. With two feet firmly planted on the ground, the figure somehow remains topsy-turvy. Perhaps it’s the lopsided placement of the aluminium Chocolatera, or of the cup, or of the seashell, or of the spoon. Regardless, I’ve known many lives that have existed in the space between these four disparate objects, and somehow they’ve always made room for miracles.

https://www.vogue.it/fotografia/article/the-alchemy-of-migration-in-comadres

http://silvanatrevale.com/the-alchemy-of-migration-in-comadres-vogue-italia